One of the things most motivating me to study my father’s ancestry and genealogy, is the disappearance or obliteration of the area where he and his family lived, probably for hundreds of years.  When I was younger, I thought my father was German, because he came from Germany and spoke German. But he was born in East Prussia. What was East Prussia, and how was it related to Germany? In pursuing that question I was led to a whole series of discoveries, which gave me a better understanding of my family’s background, as well as a massive tragic scenario of the 20th century that none of us are taught about in school.

When I was younger, I thought my father was German, because he came from Germany and spoke German. But he was born in East Prussia. What was East Prussia, and how was it related to Germany? In pursuing that question I was led to a whole series of discoveries, which gave me a better understanding of my family’s background, as well as a massive tragic scenario of the 20th century that none of us are taught about in school.

I live quite far away from the places where my father’s and mother’s ancestors lived — in fact some might say it would be hard to get further away. I grew up in the United States, and actually in that part of the US which in a sense has the “least” amount of history — the West, specifically in California, where my family moved in 1972, and where we’ve all lived ever since. California has a reputation for being a place where one can go and start one’s life over — re-invent oneself as it were. So for immigrants coming from a Europe devastated by WWII, it could be hard to find a place where one could put all that tragedy further behind, than by starting life in California.

I’m aware as well of the dichotomy between my own life at present, and the lives of my ancestors, and in particular, the East Prussian refugees around the end of the war. I live in the San Francisco Bay Area, an area which I like many who live here consider one of the most desirable places to live in the world. It’s warm in the winter, and cool in the summer. We have a great abundance of cultural and spiritual treasures in this area. There is no other metropolitan area in the US which has as much open space and parkland — I counted 150 parks in and around the Bay Area, before I gave up counting. There is tremendous ethnic diversity in the area, a climate of tolerance, and plenty of California enthusiasm and optimism.

Within a 2 to 5 hour drive, I can visit a National Seashore at Point Reyes, go hiking in Yosemite or the High Sierra trails in the Sierra Nevada mountains, drive the magnificent coastline of Big Sur, or visit the high desert in East California and Nevada. Just today I went bicycling among tree-lined shady lanes in Marin county, from Sausalito, tourist mecca on the Bay, through Fairfax, home of the mountain bike, and the town of Ross, the 2nd most exclusive/wealthy neighborhood in the United States. With this much to enjoy and be grateful for, many would wonder why in the world I would want to look back to what happened 75 years ago halfway around the world in little towns in places many people have never heard of. Why not just go out for a walk along the majestic ridges of one of the many parks in my area? Well, when I go there, I’m finding that it’s actually the experience of being on the land itself, that is pointing me towards the land of my ancestors. I think it’s the land spirits themselves who want us to know where we came from.

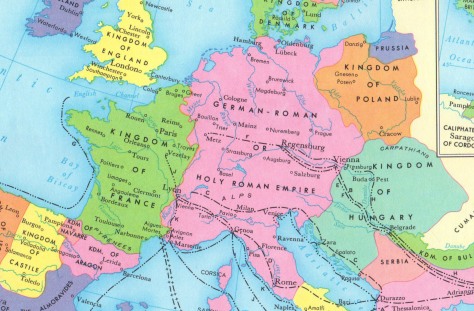

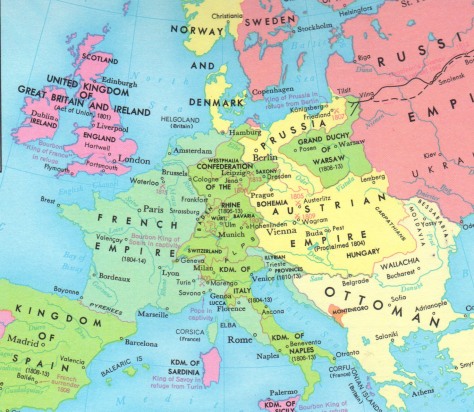

One of my first discoveries was that although the region referred to as East Prussia was most recently part of the former German Empire, Germany ,the nation by that name, itself only existed since 1871. Prior to that time this region was part of the Holy Roman Empire. But Prussia had existed for hundreds of years prior to the formation of the nation of Germany.

Christopher Clark, author of Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947, says it well: (pg xvi)

“Prussia was a European state long before it became a German one. Germany was not Prussia’s fulfillment — here I anticipate one of the central arguments of this book — but its undoing.”

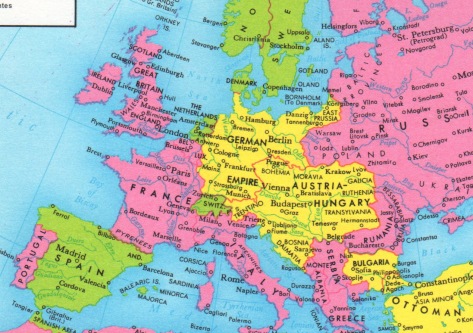

See this map showing territories in Europe in 1140 CE:

And this is Europe in 1360 CE: (the Teutonic Knights were Christian rulers who battled the pagan Prussians and eventually took over rulership of the Prussian region)

Europe in 1721:

Europe in 1810:

Europe in 1815:

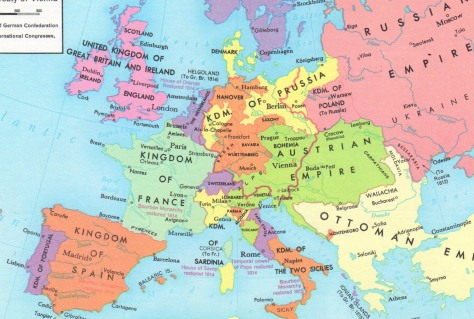

Europe in 1914:

Europe 1922 to 1940:

Europe present day:

So instead of saying Prussia was part of Germany, it would be truer to say that Germany formed out of Prussia. Moreover, Prussians were not all ethnically German simply because the region was Germanized over time and then in 1871 Prussia became part of the German Empire…any more than Russians would become ethnically Chinese if tomorrow all of Russia became part of the nation of China.

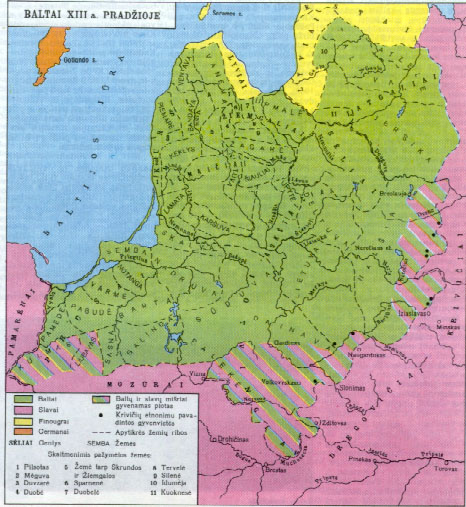

Prussia was, to be sure, a “German” region, and from what I can gather, this began in the 13th-14th century when the Prussian population began to be Germanized by the Teutonic Knights. What happened before that? In the book The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Path to Independence, Anatol Lieven writes (pg 40) that the “Old Prussians” were eliminated at the hands of the Germans in the Middle Ages. I am not clear what this means. Apparently Old Prussian was a language — was Old Prussia a nation, that was wiped out in the Middle Ages? This article explores the language relationships of the old Baltic tongues.

What ethnicity were the Prussians? And what ethnicity were my paternal ancestors? This is a puzzle. My surname, Mikuteit, from Mikkutaitis, is not German…it seems it was originally a Lithuanian name. So what ethnicity was my father? Actually based on the surname I surmise that he and his ancestors are descended not from Germanic people but from Baltic tribes, and their people were called the Preussen, or the Balts.  From pg 52 of “Forgotten Land: Journeys among the Ghosts of East Prussia”:

From pg 52 of “Forgotten Land: Journeys among the Ghosts of East Prussia”:

“The Prussians were a Baltic Tribe…akin to modern Lithuanians or Latvians.”

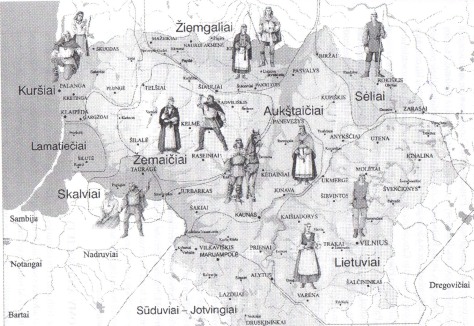

My father and his ancestors actually lived in the “very tippy top” of Prussia..not only in East Prussia, which itself was far eastern Germany (viewed by some like Thomas Mann as the wildest region of Europe) but the region in East Prussia that was to the furthest north that one could go, and still be within Prussia, or later, the German Empire. They likely descended from one of three Baltic tribes who had lived in that region from the 5th to the 13th century — the Curonians (Kursiai) or the Lamatieciai, or the Skalvians (Skalviai).

The area where my father was born (Pagrienen, East Prussia, now Pagryniai Lithuania), the town where my grandfather had his mercantile store (Kukoreiten, East Prussia, now Kukorai, Lithuania) and the town where my 4x great grandfather Jurgis Mikkutaitis lived (Minge, East Prussia, now Minija, Lithuania) , as well as the town where the church was where the families were married (Prokuls, East Prussia, now Priekule, Lithuania) were all in the region of Silute, the area of the Lamatieciai.

Living in East Prussia close to the Lithuanian border he was aware of distinctions between his German-speaking family and the Lithuanians on the other side of the border, A distinction appeared because of the use of language, as well, perhaps , due to regions that had been controlled by the Teutonic Knights, a group of Christian rulers who took over the region with the goal of converting the pagan Prussians to Christianity. However, it seems that my father and his family were ethnic kin to the Lithuanians, having common ancestors with them, the Balts, and if so they were not ethnically related to or derived from the German peoples.

This helps explain why when I have DNA test results done, in spite of the fact that nearly all my relatives on my father’s side live in Germany and think of themselves as Germans, I have zero percent German ethnicity. These DNA tests are new, and my understanding is that the attribution of ethnic-nationality may be questionable. But the results seem to support the clues shown by the surname….it seems that I am a Balt, and so is he.

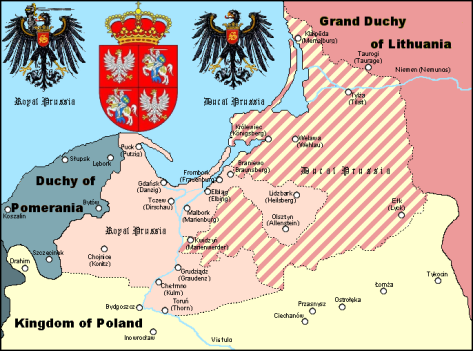

It is not clear to me, and it may be difficult to determine, how many Prussians were ethnic Germans versus ethnic Balts. But Prussia as a whole consisted of a large area , stretching from areas now within the nation of Germany, up through the top of East Prussia, a region now in Lithuania. West Prussia very likely had a different mix of ethnicities than East Prussia, closer to and including these lands of the ancient Balts and the modern day Balts. Many Lithuanians, who were certainly ethnic Balts, and not ethnic Germans, lived in the part of Prussia, which was called “Lithuania Minor.” Pg 363 of The History of Lithuania before 1795, Zigmantas Kiaupa writes, “A fair number of [Lithuania’s] people lived in another country, Prussia, called Lithuania Minor.”

In fact this term, Lithuania Minor, and the information I find about it, gives the clearest indication of the ethnicity of my father and his ancestors. From the Wikipedia article on Lithuania Minor:

The area of Lithuania Minor embraced the land between the lower reaches of the river Dangė (German: Dange) to the north and the major headstreams of the river Prieglius (German: Pregel, now Pregolya) to the south. The southwestern line ran from the Curonian Lagoon (Lithuanian: Kuršių marės) along the Deimena River to its south, continued along the Prieglius River to the Alna (now Lava) river, up to the town of Alna and hence southward along the Ašvinė (Swine) river to Lake Ašvinis (Nordenburger See) and from there eastward to the border of Lithuania Major. The region embraced about 11 400 km². The broader understanding of Lithuania Minor includes the area west from the Alna and south form the lower reaches of the Prieglius and the Sambian Peninsula, making up 17-18 thousand km² in total.

The former ethnic region of Lithuania Minor belongs to different states today. The part of Kaliningrad Oblast (excluding the city of Kaliningrad and its surroundings), a few territories in Poland’s Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, as well as the following territories in modern-day Lithuania: the Klaipėda district municipality, the Šilutė district municipality, Klaipėda city, Pagėgiai municipality, and Neringa municipality had once ethnically, linguistically and culturally been the latter Lithuanian region. Although now divided among countries, Lithuania Minor had been intact formerly, all these areas were once part of Prussia and thus politically separated from the Lithuanian nation.

Prior to 1918, all of Lithuania Minor was part of the Kingdom of Prussia‘s province of East Prussia, the core of medieval Prussia. It was a region outside of Lithuanian state, inhabited by a large population of Prussian Lithuanians. The ethnic Lithuanian-Prussians were Protestants in contrast to the inhabitants of Lithuania Major, who were Roman Catholics.

Giving the Prussian Lithuanian name first and followed by the German name, the major cities in former Lithuania Minor were Klaipėda (Memel) and Tilžė (Tilsit). Other towns include Ragainė (Ragnit), Šilokarčema (Heydekrug), renamed to Šilutė, Gumbinė (Gumbinnen), Įsrutis (Insterburg), Stalupėnai (Stallupönen).

All my ancestors definitely lived in this area called Lithuania Minor — actually at the very northern region of it, closest to Lithuania. From this it seems clear that, as my surname suggests, my ancestors were not simply Prussians, but “Prussian Lithuanians” or “Lithuanian Prussians.” And thus they were ethnic Balts, not Germans. It seems an accident of fate that they lived on one side of the border and not the other, and thus experienced the fate of East Prussia and later the German Empire rather than that of Lithuania.

Where did the ethnic Germans originate? German people existed before 1871 of course…but not in any country called “Germany.” As this article explains it, “The English term Germans has historically referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages” The article also states, “The concept of a German ethnicity is linked to Germanic tribes of antiquity in central Europe.[25] The early Germans originated on the North German Plain as well as southern Scandinavia.[25] By the 2nd century BC, the number of Germans was significantly increasing and they began expanding into eastern Europe and southward into Celtic territory….The Germanic peoples during the Migrations Period came into contact with other peoples; in the case of the populations settling in the territory of modern Germany, they encountered Celts to the south, and Balts and Slavs towards the east…..The migration-period peoples who later coalesced into a “German” ethnicity were the Germanic tribes of the Saxons, Franci, Thuringii, Alamanni and Bavarii. These five tribes, sometimes with inclusion of the Frisians, are considered as the major groups to take part in the formation of the Germans.”

This map shows the general location of the Germanic tribes, which is in the central European area of modern Germany.

When did Germans come to and first live in the region of East Prussia? How was East Prussia related to Prussia as a whole?

It seems likely that the Prussian rulers and aristocracy were mostly or even all ethnic Germans. What I gather is that the rulers, as well as the aristocracy of Prussia came from the Holy Roman Empire to the south. The rulership of Prussia as a whole was centered in Brandenburg, which was one of the 7 electoral states of the Holy Roman Empire, and is now a region in the northeast of the nation of Germany. In Prussia the term “Junkers” was used to refer to landed nobility or estate owners who controlled large parts of the land in Prussia. In his book Forgotten Land: Journeys among the Ghosts of East Prussia, Max Egremont refers to (pg 45) three of the primary Prussian Junker families:

“There were, a German friend told me, three landowning families that, before 1945, were among the richest and most important in East Prussia: the Donhoffs, the Lehndorffs and the Dohnas.”

The Donhoffs were ethnic Germans, and as this article indciates, they were:

Dönhoff, (Polish: Denhoff, sometimes also Doenhoff) was a noble German family, first mentioned in 1282, from the County of Mark in Westphalia; a branch moved to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th century and became recognized as szlachta (Polish nobility), but later mostly served the Prussian government. The main seat of the family from 1666 until 1945 was at Friedrichstein Palace in East Prussia.

Countess Marion Donhoff, who lived at the Friedrichstein estate, describes her flight as a refugee from East Prussia in her book Before the Storm: Memories of my Youth in Old Prussia. Sadly the magnificent estate was burned by the Soviet Army in 1945.

While on the subject of the Prussian aristocracy…

As I’m reading books about the history of Prussia, and the history of the Holy Roman Empire, one of the dilemmas I encounter is that these history books are heavy on the stories about the rulers, the aristocracy, the emperors, monarchs or governments — but here’s much less said about the lives of the common people. The ordinary Prussians. People like my father and his father, my ancestors.

This is a problem with “history” in general…there’s no “generic” or all-purpose “history”, that suits everyone and has everyone’s story in it. History always has a certain focus — and it’s usually focused on large events such as the changes in nations, and rulership. So history is usually the history of “the important people”…but that’s of less interest to us “unimportant” people, as much of our lives ends up not included in such stories.

I’m less interested in the stories about the rulers, the emperor and the aristocracy, and more interested in — what was the day to day life like, in this region, in the early 20th century, or the 19th, or 18th century, or earlier? What were people’s cultural traditions, values, views, beliefs? What was their relationship to their neighbors, to their lands? Did they love the wide blue sky, strewn with trails of white clouds, there at the edge of the Baltic sea? How did they feel about the forests of East Prussia? About the seashore? What was winter like, in that cold place, and how did they welcome the spring? Was it very hot in summer? What kinds of trees grew there? What herbs? What did the air smell like? What stories did they tell by the fireside? Did any traces of ancient paganism remain in these places, or in Lithuania to the north? (Lithuania was last European nation to be Christianized — very late, it held to its pagan roots…I find this appealing and I think there are some interesting stories there.)

So really perhaps I’m more interested in the anthropology or ethnology, or the mythos of this region…but all I can find (written in English..) are books of history, and some personal accounts of the flight of East Prussian refugees. So for the rest, I have to use my imagination to try to construct what may have been.

But Prussia has many meanings beyond what I am looking for….many threads, and these too may have relevance to my own family and ancestors. For instance, in the opening pages of the book Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947 by Christopher Clark, I read that one of the primary reasons the Allied occupation authorities abolished the state of Prussia (all of Prussia, rather than East Prussia specifically) on Feb 25 1947, was because they believed “the core of Germany is Prussia…there is the source of the recurring pestilence.” In particular, the unbroken political power of the Junker class, the noble landowners, was considered to have created (pg xiii) “A political culture marked by illiberalism and intolerance, an inclination to revere power over legally grounded right, and an unbroken tradition of militarism.”

And yet these “traditions” …Clark says (pg xvi) “The core and essence of the Prussian tradition was an absence of tradition.” So he points to Prussia as a sort of accidental creation, a conglomeration of disparate parts and peoples who may well have thought of themselves otherwise than as “Prussian.” What did it mean to the Prussian people to have one ruler or another, to be enfolded within one nation or another? Clark says that “Well into the 19th century there were many parts of the Prussian lands where the presence of the state was scarcely perceptible.”

One of the aspects of life in East Prussia which I stumbled across, in pursuing genealogical records, was the apparent great division between the Lutheran families on one side, and the Roman Catholic ones on the other. I’d have not given this much thought since I’m not familiar with making much fuss about what religion one follows. But in Prussia this apparently constituted a great divide. The area of East Prussia had been formed as the Duchy of Prussia or Ducal Prussia in 1525. It was established as a Lutheran duchy after the conversion from Roman Catholicism to Protestantism of Albert, Duke of Prussia, in 1525. Even in the 20th century, in the Donhoff family, they had decided that “any Catholic child…should not inherit…Marion Donhoff said that for a Catholic to be squire of Friedrichstein had been unthinkable. Roman Catholics were thought of as foreign hypocrites.” (pg 129, Forgotten Land: Journeys among the Ghosts of East Prussia)

Ducal Prussia was largely Protestant, but Lithuania was primarily Roman Catholic. In 1923, 85.7% of Lithuanians were Roman Catholic, and only 3.8% Protestant, as stated here. My grandfather was Roman Catholic, and apparently my paternal ancestors switched from Lutheran to Catholic at some point. I am curious about this and to what extent this may have to do with their living up hard against the Lithuanian border.

One of my biggest pet peeves, is when people ask what they think is a simple polite question, but which turns out to be a complicated question/issue that really isn’t appropriate to try to discuss in the 30 seconds that they have allotted to it. For instance someone is writing me a check, and they see my last name and ask “what nationality is that?” Well if I say “Prussian” they dont’ know what that means since Prussia is not a country any more, and some people have never even heard the term. They will reply , “Russian?” . If I say “Balt” they are likely to be even more puzzled. I can say “Lithuanian” , but if I do that, I am then also participating in the obliteration of Prussia that has been such a tragedy for my family — and so traumatizing for them and, somehow, also for their children. And part of what I feel called to do to heal that tragedy, is to bring Prussia back, not cover it up and make believe that my father was just Lithuanian and lived in a country called Lithuania. For that was not the truth. So when people ask, I say that my name and nationality of origin is “Prussian” but then they stand there with an uncomprehending look on their faces and no, I dont’ feel in the mood to spoon feed them on 20th century European history.

Prussia no longer exists, but the Balts do. And though I have never been to my father’s homeland, I feel a connection with it, which may come from reading about it, or perhaps from some mysterious blood-memory of the region.

And now…I want to explore what actually was involved in the obliteration of the region of East Prussia and the loss of millions of East Prussian families of not only all their property but also their homeland, as they were forced to flee the region during the Soviet invasion in 1944-1945, and were never allowed to return. This story continues in the next article, which I call “The Terrible Revenge: the Obliteration of East Prussia in 1944-1945”.

Hi.

You might be interested in the “Concise Encyclopedia of Lithuania Minor” I got it off Amazon 3 years ago. Published in 2014. Then I found another book “Studia Lituanica III, Lithuania Minor,” 1976 edited by Martin Brakas. They have different information. If I remember, there is an organization in Chicago you can join that supports Lithuanian culture.

Thanks, I enjoyed your writing!

LikeLike

Your article is great. Your reference (Forgotten Land) is my East Prussia Bible.

One thing that I did not see you mention…The Great Plague of 1709. It wiped-out 90% of the East Prussian population. About 30 years later, the Kaiser initiated a program of resettlement which brought in a lot of “German” blood. The Salzbergers from “Austria” settled in the harshest areas along the border. They readily mixed with the surviving 10% and more likely with “Lithuanians” that were immigrating in from the other direction. That is exactly my family story.

Of interest to you may be: The International Association of Germans from Lithuania (www.germansfromlithuania.org).

Also: the book “Der Pest in Ostpreussen” (The Plague in East Prussia).

It is in German, but I have published a translation in an easy-to-read spiral bound format. I can send you a copy for $15.58, all costs included. In this era of our own plague (Covid), it makes very interesting reading on its own.

LikeLike